Meet the speakers: John Roesch

An interview with John Roesch: Lead Foley Artist at Skywalker Ranch and co-founder of Audible Bandwidth Productions.

Q&A hosted by Meryn Hayes & Cory Livengood.

Read time: 15min

Meryn:

Meryn Hayes: For those who don't know you, could introduce yourself.

John:

Sure. My name is John Roesch and I'm a professional Foley artist that has been working in the film business for almost 44 years now. Playing in a big sandbox, making sounds that if I do my job right, you don't know I've done.

Meryn:

Foley is one of those jobs that people don't tend to appreciate until they hear a movie without it. We're really glad that you're joining us to talk about such an important part of the entertainment industry not many people know about.

John:

Well, I'm glad I am too because like you say, Thor is running towards saving the day, so to speak, and we're close up on his feet and he's running really fast. And wait a minute, if there's no sound there, I'd be like, "Is this guy really a hero?" Or same thing for a gal. So our contribution, and of course we're a small spoke on a big wheel, can lend credence to giving a sense of reality because of course, as we know, all filmmaking is just that, it's smoke and mirrors. But we want to make sure that you, the audience, feel that you're completely immersed in it and it's "real" to you.

Cory:

I'm curious about how you found yourself in this part of the filmmaking process. I know you dabbled in acting and directing at a younger age, how did those skills translate to Foley if they do at all? And how did you end up in your big sandbox, as you say.

John:

I was an actor in high school and I went to NYU film school and then I went to the American Film Institute thinking I'll be a director. And just so happened that a gal that did my script supervision for the one AFI film I did, she said, "Hey John, I need help doing sound."

And next thing I know they look around and say, "Well, this guy's got sneakers. Are you a runner?" I said, "Yeah." A guy goes, "Well, this film has running in it. Come to the Foley stage." What is that? The Foley stage? "Come to the Foley stage." Okay. So I show up and they say, "See that guy on the screen there?" Yeah. "Okay, run for him." All right, so I ran across the room. They said, "No, no, no, you have to run in front of the microphone. Like, "Oh, I see." They're going to record the sound. I went home that night and I thought, "That is the stupidest job ever."

And next thing I know, I get a call from her husband, Emile and he said, "Hey, I really like what you did. Can you come in tomorrow to this other stage, do Foley?" I thought, "Okay, I guess." So I'm leaving my place in Venice, California and I had a convertible, I was backing up and, oh, there's the landlady. "Hey Joaney, how you doing?" She says, "Hey Johnny, where are you going?" I said, "I'm going to the Foley stage." She's not going to know what that is.

Cory:

Yeah, of course!

John:

She says, "Hey, that's what I do. They just fired somebody there. Maybe they'll hire you."

Cory:

Your landlady?

John:

I thought, "Man, has this got kooky or what?" I'm not so sure. So I said, "Yeah, okay, sure. Thanks, Joan." So I drive off and do that. I get home and on my answering machine, the low budget film I was going to AD got pushed back out to three months and rent was going to be coming due. I thought, "Well, maybe I'll just call Joan and just see what happens." And that was 44 years ago.

Cory:

That's incredible.

John:

To answer the second part of your question, it indeed is important to have a bit of the thespian in you because the hardest thing to do are actually footsteps, to give them life. And to do that, you have to kind of act, if you will, that part of whoever's on camera. Are they a little drunk? Are they the hero or heroine or are they the bad guy or the villain? You're trying to embody something that's not there. You're trying to give soul to something that's not there. And that really comes from acting. So yeah, there you go.

Cory:

Yeah, that's interesting. Anytime I've seen video, probably of you before we met, of course, on television of Foley being created, it always felt very performative to me, like an actor in a way. And almost no matter what sound is being created, it's always very interesting.

John:

Yeah, it is by definition. In fact, it's called Foley named after Jack Foley, that is, in deference to him. But it was not called that. It was called the sync effects or the sync sound effects or the sync stage, or actually the A stage was a stage where they did a lot of what we now call Foley. But the true definition of Foley is custom sound effects. That's a differential between a jet plane's engines going by and then somebody grabbing the throttles with their hands and pushing them forward to make sure they clear the obstacle in the distance. Grabbing the throttles is unique to that moment in that film on a per-film basis, whereas the engine spool up, that might come from a library, it could be used in many films. But Foley has uniqueness all unto itself, hence the, as you just said, the performance aspect to it.

Cory:

Do you recall seeing or hearing a film that really inspired you from an auditory perspective when you were sort of starting your career?

John:

Oh, I say 2001 would have to be one of those. Just the way it's portrayed. Space and all that sound kind of in the background and then bursting into the back into the craft. And there's no sound there. I mean, it really kind of leapt forward for me, and I'll tell you all this now, I didn't really pay that much attention to sound until I got into Foley. I was more interested in like, "Okay, how do you block this scene?"

But of course, as time goes along, in fact the measure for me, if I'm watching a film and I start picking apart the Foley, that means I don't like the film.

Meryn:

Is there a particular project looking at the portfolio of work that you've done in your 45 years that you hold as one of your favorite projects or a few different favorite projects, and what would be on that list?

John:

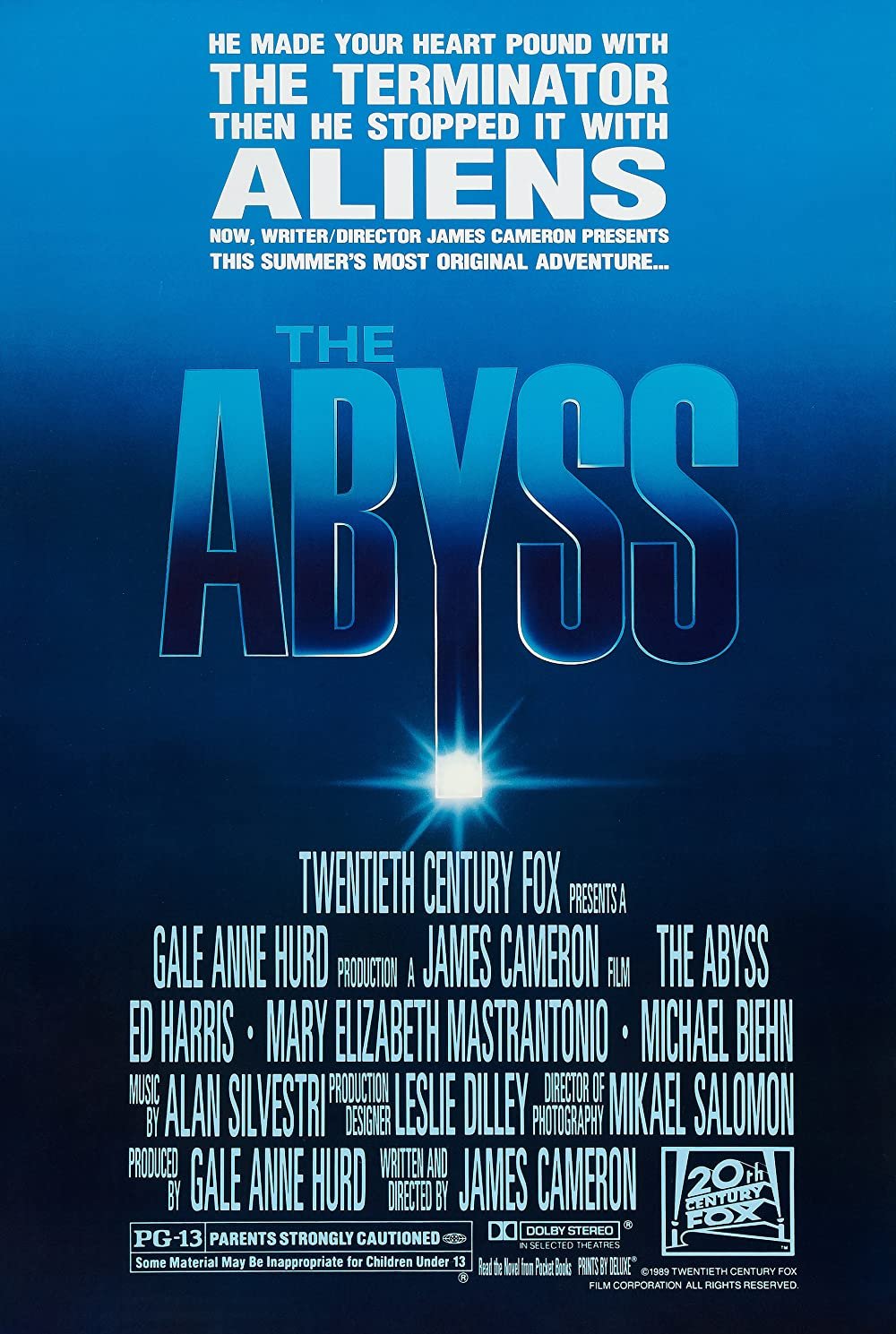

I'd say there are three or four if I could go into that many. One of the hardest ones was a picture called The Abyss and that dealt with a lot of underwater water. And that's extremely difficult because that's an all-encompassing sucking of the frequencies, if you will. So we had to really experiment with that to come up with what's going to work. And of course, James Cameron, you do not want to disappoint him. And I've got a story which I'll probably hold back, maybe I'll share it during the meet and greet. We'll see.

Cory:

Now I'm curious.

John:

Good. I’ll whet your appetite. Another one, and I'll kind of put those two together would be Back to the Future, and Who Framed Roger Rabbit,. We’d been in a bit of an arc where Foley was really not used that much. And during those years, I call them the Camelot years of Foley, we were given license to do everything.

So when the plutonium is being sucked into the plutonium motor, if you will, on the back of the DeLorean, that was us using glass and certain effects in even a blooping sound. If you take a cardboard tube and you kind of hit it on one end, it can make a [bloop sound]. Things like that, which typically you wouldn't do in a film.

And Who Framed Roger Rabbit, there again too. You had not only humans walking, but you had toons. So we had to do a whole section from them, not only their footsteps, but their props. And that was really just a whole heck of a lot of fun.

One that I think is very important, would be Schindler's List because that's a period of history which we should never forget, I think.

And of course these days talking about animation, Soul is a particular project which I'm absolutely thrilled with. It really embodied a lot of things that are difficult to do for animation, and they were just so beautifully done. And I'm not talking about our aspect per se, although we had a chance, again, we had the time to do it.

And of course, you could take a Marvel film, something big, over the top. Think Guardians of the Galaxy type thing. So those are fun.

And last but not least, there would be what I'll call the student film. And I did a film many years ago called In The Bedroom and Todd Field was the director. And that was something we really did kind of bootstrap that not having much money, if any. And we did that kind of in the off hours because I believe that I... I saw it and I knew this is an incredibly good piece. By the way, if you haven't seen it, I would recommend it. This guy's going on to direct Tár and he's up for six Academy Awards.

Cory:

When you first get a project, walk us through what that process is from the very beginning when you're just starting up until you get to “we're in the studio now, we're making the sounds”.

John:

Okay. Well, we like to beforehand get a look at the film if possible. If we can't look at the film, we would at least like to get notes from the director. And there's something called a supervising Foley editor, he, she, or they, that are given guidance by the supervising sound editor, sound designer. Like, "Okay, in reel one, we want to cover these feet. We want to have you do the pickup of the special sword, yada, yada, yada."

So they will impart that information to us and also talk about the design of it, so to speak. Let's say in animation, if it's a cat running around, if it's a main character, even if there's not a little license or bell or something on it, we might try to cheat something there to give it life. But is that contrary to what the director wants? And then when the day comes we start, we'll look at the reel again and we'll have what are called queue sheets. Which will detail out Heidi on channel one, Dave on channel two, Christo the Cat on three. It'll detail out what we need to do. Footsteps first, then prompts, and then movement, if any.

When I say movement, it could be a leather jacket, which is... Let's see, a Guardian's [of the Galaxy], they wear those type of things, so that would be a separate prop. Whereas if we're just covering general movement, let's say for an animated feature, we might just do a one pass cover.. And that's how we proceed during the day.

And it could be that the director said, "I'm not really sure how I want Sally's footsteps to sound there and overall the feeling of her character." So we might try variations, we might try tests. So we'll do test A, B, C, D and just send them off. We won't say what we used. Test A's a tennis shoe, test B is gloves. We'll just send them off and then the director or whoever will get back to us and give us their feedback and we'll go from there. And that'll be established throughout the film.

Cory:

And how closely are you working with the director? Or is there any case where you're working with the music composer or is that a pretty separate situation?

John:

Typically, music and Foley, the twain don't meet. The only time they do in a sense would be, let's say with David Fincher, because he's very involved in all aspects. So he'll make sure that Trent Reznor or whoever is doing the sound is involved with Ren Klyce, who's typically who he uses. And then they will filter down to us what they need.

So typically we'll start a film, let's say... I don't know any of the recent films. Strange World. And maybe a week into it, they'll fly up to Skywalker [Sound] and sit down with us and play some stuff back. They'll play back some of the Foley and review it and if there's any changes, let us know. Now, mind you, again, if there's something we think we're really not sure about, we'll send a test down first to make sure we're on the right track, because time is of the essence.

Meryn:

And what about in terms of how long a project might take? I mean, I know it's a process, but say for Strange World, for example, I mean are we talking weeks or is it a one week and you're done or is it months?

John:

No, it's typically two days, maybe three days a reel. Now, Strange World, if I recall correctly, I think that was 18 days, all told. Whereas the last picture we just did, unfortunately, I can't name it. It's volume three, I can say that. I think that was 20 days altogether. And Pixar films tend to be even longer, like 25 days, which is really necessary because again, in animation you can get away with things that you really can't do in live action to some degree, which is wonderful.

Meryn:

I love that you said 18 days was long because in my head I was like, "That feels very short." So I think that's just a good reference point.

John:

Well, I don't know that I'd say it's long, but I'd say that probably is enough. I mean, given our druthers for animation, any project that comes in, we'd like 25 days because then we know it's going to get covered. And we also work of course on commercials, on video games, and a little bit of television that is streaming. Worked on Andor. That was three or four days per episode, if I recall correctly, which was necessary. Again, because I have a lot going on there. But if you're a Star Wars fan, I highly recommend that.

Meryn:

Yes, we are big fans.

Cory:

Maybe one of the best Star Wars shows that's been put out there yet. In my opinion, anyway.

John:

I would agree and I think season two's going to be even better.

Cory:

That's great. Looking forward to it. I'm sure you won't give us any spoilers, but...

John:

My lips are sealed.

Cory:

Well, speaking of Star Wars, I mean, I'm definitely curious about your process when you're coming up with the sound for something that's totally fictional. A laser gun or a spaceship or something that doesn't exist.

John:

When I see something on the screen, I hear its sound, so then I try to translate in my mind, well how do I create that sound? So like you say, if I'm picking up a weapon that's specialized or loading it, what would that sound like? And is it a used world like Star Wars or is it a clean world like Star Trek?

I'm going to want to embody the world itself and stay within those contexts, within those confines, I should say. And of course, the great thing with Foley, there's no rules. The only rule is there are no rules. So you can try something. If it doesn't work, do something else. That's the beauty of it. And so that would be in essence the process.

Meryn:

Is this a professional hazard where you're just going about your day, you're in your kitchen and you put a cup down and then you hear something and you're just like, "Yeah, I need to write that down 'cause that sounds like..." Your friends and family just like, "Oh, John's always stopping what he's doing and he's writing down that piece of paper that fell, sounds like a bird's wings or..."

John:

Every once in a while, something will happen where something will be delivered or who knows what, and it gets pushed a certain way and moved a certain way and I go, "Wow, I'm going to have to remember that and take it into the stage." And conversely, when we're working on a film, if we establish an unusual prop, I'll take either a text note or a picture of it or even do a video. In fact, Shelley might stand over me and I'll explain what I'm doing, how I'm doing it so I can recreate it throughout the picture and vice versa for her.

Meryn:

Yeah. That's amazing. Is there something that's a really strange sound that you can recall...

John:

Well, I'll tell you the Abyss story then 'cause I think it was probably the most difficult sound, one of the most difficult sounds I've ever done. In the picture, Ed Harris is sitting down in a suit that's now going to have a helmet latched on, and it will fill up with liquid, literally starting at his chin, up over his face, over his head. And he'll then breathe that in.

And the reason for that is that it's going to allow him to go to deeper depths than one could without being crushed. Anyway, that's the theory behind it. So there I am, looking at this going, "Okay, now if I hold a helmet upside down and I take water and pour it in the top, it's not going to sound right. It's not going to sound like a muffled helmet, it's going to sound like [clear]. So how do I do that?

I thought and thought and thought. The night before our last day of Foley, I had a dream. And I dreamed how to do it.

And the way to do it was micing in a certain way, where I was stealing the ambience of a helmet and yet having a way to pour into something also that would approximate a helmet so I could literally get the proper going from low to high up over his head. And then on a separate channel, I took a straw and did a couple bubbles to come out of his nose. Strange job, I know.

Cory:

Are there any big differences in your mind when you're working on a film versus television versus a video game?

John:

Well, yes, certainly a video game has a routine all of its own. And that could be, are we doing the cinematics or are we doing the in-game assets? So if it's the cinematics, we approach it just like a feature film. If it's in-game assets, we might do Batman's cape or 2 or 300 variations of it, one after another. Or footsteps just landing on a surface, on metal. We might do 50 or 100 of those because again, during game play, randomly it'll be pulled from the bucket as to what particular sound that one step is.

So that's very intensive for a Foley artist team to do. Versus if you work on a feature, it's kind of tag team, if you will. And now mind you, television is a bit of a different beast, because not so much when I mentioned about streaming, at least at Skywalker, but television itself doesn't typically have a budget that's as friendly as one would hope.

Meryn:

You started talking about the team just there. I mean, on average, how many people are kind of working together on this? Because it sounds like... I mean, you mentioned earlier it's a team effort.

John:

Totally. The day starts as a team and it ends as a team because even if I'm doing footsteps, Shelley is either helping run the sheets with Scott or Scott's what we call driving. He's telling me where we're going to go,. But she might be making notes for shoes for herself or certainly for doing props. While she's out doing props, I'm in another area looking at a monitor, looking at the actual reel, making notes for myself going, "Okay, so this cut... Actually we're cheating the hand grab of Thor on Loki." we’ll not actually see it, it's just literally on the cut. So I'm going to approach it a little differently than I would if I see it. Or the communicator that's being picked up and is being flipped out that has to have a certain sound to it because I'm seeing some detail here.

Mind you, while she's out there working, then we switch. So she'll do the same thing. She'll be in the monitor checking her notes while I'm actually performing. So that's exactly what happens. Does that happen at all for all of Foleydom? It's hard to say. You have a younger generation that I don't know that knows the joys of having a team.

So point being, I think it's a lot harder in a sense for younger Foley people, especially if they're just working by themselves.

Meryn:

That leads very nicely into the next question that was going to be about advice for younger Foley artists. And maybe the advice is to find people, find your team. Is there any other advice or things you can think about for people who might be early on in their career or wanting to get into this field and they don't know how?

John:

Certainly if one wants to be a Foley artist, I think number one, they need a good background in acting. Take some acting classes. If you can, direct some one-act plays and read a lot. Read Shakespeare, read just a lot of good books and watch films. AFI top 100. Pick them apart. Why do you like this? Why do you not like this? Take a television show, like Friends, and then just put down something to walk on. Because typically Friends is people walking in from off stage and stopping or leaving or maybe walking upstairs, so you can practice getting sync, not worried about the sound that has to really come on a Foley stage.

And of course Mom and Dad out there won't necessarily like this as much. A half hour a day of a first-person shooter video game is okay because you're literally training your eyes not having to look down at your hands, which is extremely important for doing Foley, performing. And, you'd want to have aerobics in your life along with stretching. Aerobics-wise... Swimming, you can't beat that. All those things are really mission critical to be an excellent Foley artist.

Hopefully then you can get on with someone who can mentor you and learn from them. And then also try out your own thing because nobody has the actual answer. It's in a sense experimentation and you'll find your path that way and having a belief in yourself and also being open.

I didn't go out and start out to be a Foley artist, but look where I am. And I don't say this to dissuade anybody from being a Foley artist, I'm just saying just be open. Hopefully you'll have a love of it because I think it's no longer a job, it's a career. And then surround yourself with people that'll hold you up. Because you don't want to be with people that are jealous, either overtly or covertly. That'll do you no good.

And those are people you really don't need in your life because there are people that are going to want the best for you because they realize, "Hey, if we work together and you're doing great, I am too." And why not? Especially these days in this world. Good grief. Hey, I'm going to be 69 by the time I see you all. I've learned the four words, "Be happy, love fiercely." That's it.

Cory:

That's great advice. it's just really interesting and something I hadn't thought of until we met and started talking about this stuff, how the hand-eye coordination, the aerobics, the performance of it and all of that is just a very different viewpoint when it comes to post-production and even audio, to a degree, which is really, really fascinating. It's just so much exercise, which is great.

John:

It's helped a lot, I'll tell you.

Meryn:

I have a burning question from my five-year-old who we watched Strange World for the fifth time last night. What sound does Splat come from? The character?

John:

Splat comes from many different parts. Now, we did some of the footsteps... Let's see, I guess you could say Splat, Foley-wise would come from a bit of a wet shammy, but that's a very small part of what Splat was.

Meryn:

The noises that come from Splat might be my favorite in that film because it's adorable. So everyone should go watch it. We can’t thank you enough for talking to us John!

John:

Well, I wish everybody a wonderful day.

John:

Yeah, absolutely. This was a great way to have a Thursday. Can’t wait to see you in July!