Takeover Tuesday with Jardley Jean-Louis

An interview with Jardley Jean-Louis an NYC born multi-disciplinary artist living and working in Queens.

Interviewer: Matea Losenegger

Read time: 5min

Matea:

Hey Jardley! Thanks for lending us your time. Can you please introduce yourself?

Jardley:

Hey! I’m Jardley Jean-Louis, I’m an NYC born multi-disciplinary artist living and working in Queens. I work in illustration, animation and film and center my work on depicting stillness, education, and under-represented identities and subjects.

Matea:

What inspired you to become an artist and how did you get into the motion design space?

Jardley:

It’s funny, I’ve been an artist since I was a kid and was going to say nothing inspired me because this is how it’s been forever. But I have a memory of being really young and there being a boy who was a really great artist in the class, me aspiring to be that good and taking him on as my mentor. So, that kid and my perseverance to get really good.

In terms of motion design, I think in the back of my head while I was pursuing just art, I wanted to get into the animation space. As a kid that meant the goal of having my own show on Nickelodeon and a film for Disney when I grew up, and later and more concretely, learning more about motion design as an Illustrator’s Assistant for a one-person animation studio while in college. That was my first art job. While my role there was to produce character/background design, the CD also invited me into the depths of script-writing, storyboarding, and animating background characters. Getting that well-rounded experience and seeing the final animation which felt like magic to me, was enough to start me on my own journey of honing my animation skills and looking for my own clients.

“Mementos.”

Matea:

How would you describe your artistic style and what are some key themes and messages that you explore in your work?

Jardley:

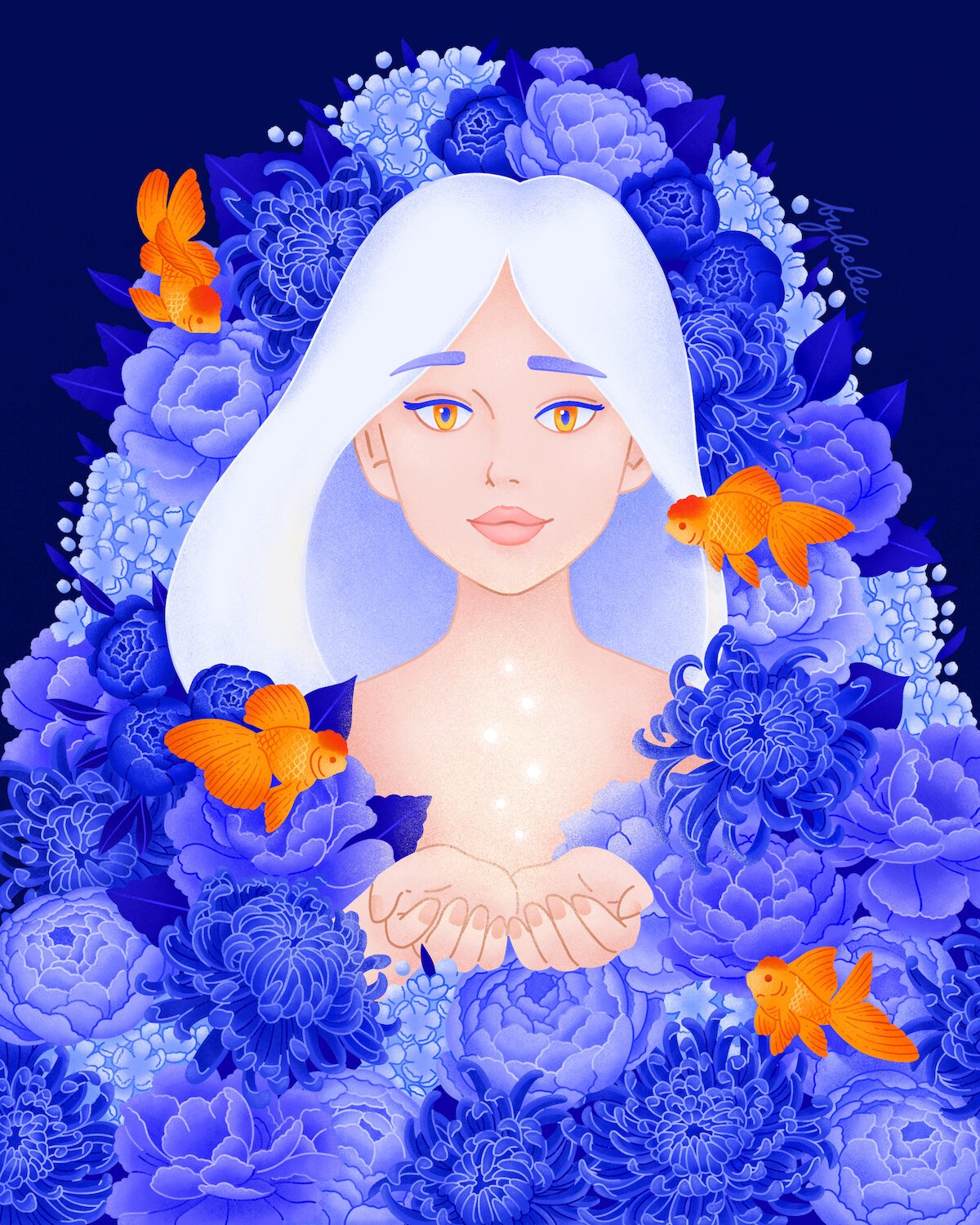

My work is very character driven and intent on building a mood especially with lights and shadows. I also without intending to, use a lot of deep rich colors. I work digitally these days, but my work has been described as painterly - which is great to hear because my foundation is in traditional painting and drawing. So, that’s unintentionally translated.

The key themes and messages I explore in my work are quiet life moments that speak to the reality of life, education, and under-represented identities and subjects.

Matea:

Can you walk us through your creative process? How do you come up with new ideas and what techniques do you use to bring them to life?

Jardley:

On both client and personal work - the creative process is dictated by the brief or idea and what mood and feeling the work is trying to convey. On client projects I’m zero-ing in on the themes and message the client has shared with me and the key words in the script that define each scene. On personal projects, I have an idea and I’m looking to draw it out through thinking of what type of composition and lighting accentuates it.

An exercise I do is dump every idea (including a ridiculous idea) onto my notebook. I believe that writing every single idea, not criticizing it, and therefore dismissing it, frees your mind to be more creative and find its way to a strong concept. If you’re constantly cutting an idea off at its legs, you won’t feel safe enough to explore and trust you’ll find an idea.

I then work through concepts by sketching them out and writing questions I have for myself. I find the notes especially stimulating.

I also review my long list of Flickr reference images and spend a lot of time on Behance looking for inspo.

Matea:

How different is your approach to client work vs your personal projects?

Jardley:

Well with client work it involves more pre-production than I do in my personal projects. That involves deciphering the script or brief and providing tangible materials such as moodboards, sketches, style frames or mockups, and storyboard animatics. In my own work I do less of that - the tangible materials. I’m typically holding an idea and composition in my head. I’ll look at a ton of reference images and then go straight into creating it in photoshop or after effects when the pieces feel right. For both, I also am finding the color scheme while I’m working - most times I have an idea of colors, but it’s not settled until I’m working on it.

However, since my recent solo exhibition, I’ve started to see the reason for sketches in my own personal projects. It helps to remind you of what the composition is meaning to be and by having it out on the paper, you’re able to see if it’s working or not rather than just going straight to final. Finding out the imagined concept didn’t work bit me in the ass one or twice on this solo.

Matea:

Huge congratulations on your recent solo exhibition "Joy - This Place I Land." What was that experience like and are you interested in working on more gallery work?

Jardley:

Thank you! The experience was incredible, I’m glad. I was selected as a ARTWorks Fellow for Jamaica Center for the Arts and Learning’s 10 month residency and the solo exhibition came from that.

So it was a 10 month process of figuring out what scenes best represented my theme: what does joy and thriving look like in everyday life. Especially being Black.

Originally I had 6 pieces + an animation I planned, but upon revisiting the gallery space and seeing how much space I had, I added 2 more illustrations. Getting to show what joy is for me, which is really just love in life moments and witnessing how much it resonated with folks meant a lot to me.

I’m not really interested in becoming a gallery artist. I’ll have my work in shows here and there as long as it makes sense to me. Same for residencies. I’m not actively pursuing either. I view it as avenues that are available to me as a creative. Never just confined to one avenue.

“Bart Simpson”

Matea:

I know it's difficult to choose, but do you have a favorite piece in the show and what makes it stand out in your mind?

Jardley:

I have two pieces that stand out for me. “Heritage” for its family ties, warmth and sense of just belonging and “To Be With Friends.” for all the love, lightness, and thriving I continually want for my life.

Matea:

Where do you get inspiration? Are there any particular artists or movements that have impacted your work?

Jardley:

I get inspired everywhere. Walking around and looking at things, overhearing conversations, being with people, looking at the work of fellow creatives, taking in my apartment, processing my life, tv shows/films.

Artists that heavily impact my work are Rebecca Mock and Katharine Lam. Particularly for creating a mood and for their use of lighting. Also Pat Perry, for the still and simple moments of life.

Matea:

How do you stay motivated to create your own work in addition to client projects? Do you have any tips for burnout?

Jardley:

I won’t say that I consistently create my own work and do so alongside client projects successfully. I don’t have a routine. Sometimes it happens that it’s a particularly slow time so I have room for my own work, or there’s an idea I want to get out, or mentally I’m in a space to put the work in and things just flow then. I try to honor where I’m at. I guess I stay motivated because producing client work isn’t my end goal for my career. I want the ratio to skew wherein majority of the time, the work I’m producing is mine. It’s what I’m known for and it’s how I make a living. I still plan on working with clients, but I think my voice and creative project being the end goal is more fulfilling.

For burnout, my tip is to honor it as best you can. When I was a permalancer, that meant speaking up that I was taking some mental health days for myself. When I’ve been working non-stop on client work that means taking as much time as I can in between client work. If I’m on deadline, but am already burnt out and a concept isn’t coming or my brain is frying, I try to take chunks of time during the day to just chill out. Honor it as best you can.

“Heritage”

Matea:

Any upcoming projects you're excited about?

Jardley:

I recently wrapped up an animation where I was the illustrator on it which I’m excited to see in its final. It’s about the stained foundation of America.

I have a personal short film animation that I’m currently researching and world-building on on the early years of the AIDS epidemic and Haitians.

Meet the speakers: Amanda Godreau

An interview with Amanda Godreau, a Puerto Rican multidisciplinary artist. Through bold work, Amanda lends her creative vision across multiple mediums, showcasing her appreciation for the beauty of design throughout unique spaces.

Q&A hosted by Meryn Hayes and Ashley Targonski.

Read time: 15min

Meryn Hayes:

Amanda, welcome. For those who don't know you, I'd love it if you could give a quick intro and how you got into motion design.

Amanda Godreau:

I got into motion design completely by accident, which is something that I always love to tell people. I think once you're in it, you really start to see that it's everywhere. I went to college originally for coding and then transferred to college in Florida for graphic design, and they just so happened to have one of the best motion design programs there. And a really talented professor found me, and said, "You need to change careers."

I was like, "All right." And it was just, it's been a whirlwind since. I feel like every single year I've learned something really different.

Meryn Hayes:

I think many people can relate to finding their way into this industry. I think this industry gets people from all kinds of career backgrounds, which I think is one of the really unique things about it.

Amanda Godreau:

I completely agree. I think throwing out the plan has been such a good thing for me. I think even as of six months ago, what I had planned just completely flipped. And I think learning to embrace it has only been to my benefit. It's been to the benefit of people around me, and I think it should be discussed more. I don't think you can plan for most things in life.

Meryn Hayes:

Absolutely. Well, that leads really nicely into my next question; so you graduated about a year ago, right? Did you have a lot of expectations of what was going to happen after graduation? I mean, what was the plan?

Amanda Godreau:

I feel like I wasn't entirely sure what I wanted to do when I graduated. To be completely honest, I didn't even know if I wanted to continue in the same field. I was heavily considering shifting to another industry altogether. And I knew the one thing in my plan was to rest. I came out of art school extremely burnt out. And that's something that needs to be talked about more. There’s something that TJ touched on last time at Dash Bash, I remember being a student watching his panel, and that it was a very big moment for me. I remember thinking "Someone who has been in this industry for so long is acknowledging it, I need to pivot and think about how to build rest to what I'm doing."

That was the plan post-grad, was to rest, and recharge because I knew that the aftermath of being so heavily focused on my career. To be able even to say you have a career in college is crazy, right? I realized I needed to allow myself time to be a 20-year-old in my early twenties, and as a result that’s been really beneficial to my career as well, I think.

Meryn Hayes:

That's so important because as we all know, finding inspiration in your art, in your work has to happen outside of your computer, outside of your desk. Being inspired by things, having a life, and especially at a young age. Feeling like you have the freedom and ability to find who you are because at that age you're still figuring out, "Who am I?" I mean, I'm still figuring out who I am. You need space in your life and to not have everything planned out in such a way that it constricts you from figuring out who that is before you really even started.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah. And that's all to the benefit of the art. I feel like the moments where I had the hardest time making art, creating art, and making art that I was proud of were the moments where I was pushing myself so much that I had nowhere to draw from. If you're not connected to yourself first, you can't make something that's supposed to connect with others. So, I laid aside any professional aspirations I had. Including what studios I wanted to work with and what I wanted to do. I laid it to bed five to six months after graduating because I realized that even if I could do it, I was really going to enjoy doing it. And ultimately, I feel like enjoying the art you're making and your work is the top priority.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, absolutely. And in terms of finding your style and what brings you joy and the work that you do after graduation, what was your approach to finding that?

Amanda Godreau:

Finding the work that I enjoy making, I think, for me, has had to do with connecting with so many different people and so many different types of artists. My number one goal this year was to chat with people, learn, and view outside of my lived experience. And that inspired me to make many choices in how I approach my art. I was really fortunate last year. I got to go to Portugal for NFC Portugal. It was just this gigantic NFT conference, no motion designers, I think I was the only of the few ones there.

Even though personally I'm not active in the NFT community, I got to chat with people who are so invested in it, and at the end of the day, everyone's making art, right? Connecting with just people as artists outside of a commercial or traditional background has been so valuable.

Something I started to do as well was to connect with smaller BIPOC and female-owned brands, and I've been working one-on-one with a couple, developing renders pro bono, and just making art with women that I connect with. And that's been a really good way for me to give back, push my creative vision forward, and also feel like I'm doing meaningful work that serves an ethical but also spiritual purpose for me. And that's been really good.

Meryn Hayes:

That's amazing. How were you making those connections with artists after graduation?

Amanda Godreau:

I was chronically online in undergrad; a lot of these connections were friends or people that I had connected with during this time when everyone was online because of the pandemic. I've gotten to travel so much and be like, "Oh my God, we've known each other for four years; we've never met, let's hang out," And that's led to even more connections and more people. And I feel like it's snowballed into this gigantic network of people that I feel like I've known for years, and also simultaneously feel like I don't know it all.

Meryn Hayes:

I think that's one of the things that I am just so appreciative about this industry and this community is that willingness to just chat. I mean, my background is in photography. I ended up here because I found myself at a marketing agency here in Raleigh, which is where I met Mack and Cory who founded Dash. But before I joined, I had been involved in animation and live-action projects, but this whole motion community was completely over my head. And so, as soon as I joined, I just realized how kind everyone was and willing to share their experiences, which I just feel is pretty rare in most industries, but especially in art. I just can't imagine photographers, I don't know, sharing their problems or I just think it's a really special place to be able to find that.

Amanda Godreau:

I agree. I think this community is extremely generous. I think this community overall is extremely humble and I think it's really open. I think there's a lot of room for people to grow in all sorts of directions and I feel like you can almost always find someone to relate to in at least some sense. And everyone's cheerleaders for each other. I don't think, at least the people I intentionally try to connect with and stay in touch with, I feel like everyone's so proud of each other at the end of the day, not just for professional reasons, but for artistic reasons, right?

Something I've tried to make a very different distinction this year is the difference between being a designer and being an artist. I think before this year, I would be a designer and people would ask me, "What's your style?" And I'd respond by saying, "I don't have a style. I follow a brief. I'm a designer, I'm a problem solver." This year I'm getting to explore an artistic side of myself and acknowledging that side, I wasn't open to it at the time, and just starting to understand the difference has been a really big conversation among a lot of people in the community. I think it’s been a really great one.

Meryn Hayes:

Absolutely. I mean, again, going back to your whole life, you're given briefs in college and growing up, about who you're supposed to be or what you're supposed to be doing. And so, for the first time, you're actually trying to figure out, "Who am I?" Both personally and artistically. So, really giving yourself that space on both sides of that coin is just so important.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, I agree.

Meryn Hayes:

So, timeline here, so you were in the middle of college when the pandemic started?

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, I was in my sophomore year. I had done one year in person, at that point II had done one semester of After Effects and one semester of Cinema 4D when then the whole world shut down. That was completely unexpected.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah. And so, how do you feel, I mean, it's all you've known, so hard to compare, but how do you feel that changed your trajectory of what you were learning or how you were learning or learning from other students?

Amanda Godreau:

I think it completely changed the trajectory of my career for sure. I think as for socially, I don't think it left me with much of a college experience or much ability to connect with other people, but that's a completely different topic in itself. I think what that period of online learning gave me was my career. I started freelancing full-time after my second internship. I completely attribute that to the amazing opportunity that Gunner gave me. They hired me as their intern that summer. I wrote them this very dorky email being like, "I really want to work with you guys, and I can work remotely. I'm super good at it, I promise.

I was able to freelance every single year after that. I think about my choice of going freelance after college versus taking a staff job often.

Had there been more in-person opportunities to be in a studio with people collaborating, looking over monitors, going staff would've been more of a consideration for me. But at the end of the day, when I graduated, everything was still Zoom-oriented. I felt most comfortable staying freelance and meeting new people and teams.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, that's really interesting. We were down at SCAD at CoMotion back in March and talking to students who are about to graduate and obviously, there's a lot of opportunities going in staff or freelance and trying to give them some advice about options. And I always like to be very clear that I only have ever done 9-5 staff jobs, agency jobs, or in-house. So, I don't have the freelance perspective of freedoms, so I can only offer it slightly one-sided, and I hate to sound like Boomery, but I just know that early in my career I learned so much by sitting at a desk next to somebody just looking at asking questions, looking at their screen.

And so, part of me just feels for students who are graduating who don't have opportunities like that, or like you said, even now a lot of staff jobs are remote or hybrid and that's like, "Why am I going to go into the studio to then remote into somebody in Wisconsin or California?" And so, just finding out what people want to get out of that first experience after college and trying to find whether that's freelance or staff.

Amanda Godreau:

I think the industry, in general, is going to find itself with a very different type of workforce because of this, I personally have the opinion that it ripples down 100%. You have people two years before me, so many people who graduated in 2020. The industry was so focused on just how to switch and not lose these giant pitches and how we work, which fair, needed to happen but left a gigantic question mark on how students and upcoming graduates view the industry.

Meryn Hayes:

Good leading question. I was going to go, "How, Amanda, do you fix it?" But you're going to tell us in at the Bash.

Amanda Godreau:

Going back to Ringling in March. I found a lot of good insight. I did this amazing long two-day portfolio review with Doug Alberts from Noodle, and we got to talk one-on-one to students, and I really asked them, "How do you feel about this community? How well do you feel about jobs? What's your experience? Do you feel prepared as a senior?" And I got to get all this amazing feedback that I think is really informing how I'm trying to shape this presentation.

I had an existential crisis when you guys asked me to speak because I was like, "How am I supposed to speak to a room of people who have decades of experience over me?" I think my art is awesome, I'm my art's number one cheerleader, but we're in this very interesting time where there's so much more conversation to have about what we can do to support the youngest people in our industry and how that is essential for the better of everyone. That's what I'm interested in right now.

Meryn Hayes:

I mean, well, now I feel bad that we caused an existential crisis.

Amanda Godreau:

No, it was a good one.

Meryn Hayes:

Okay, good. But I think we would be remiss to not think about the younger generation. I mean, there's two schools of thought that we need to figure out how people retire in this industry. That's a whole other thing. But on the other side of that coin is figuring out what has changed in the last two, three, four decades as people have come into this industry. And hearing from people like you or others who are just getting into it. I mean, you have a valuable perspective, and if we don't account for both sides of that coin... We need to figure out how to include all of those ideas.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah.

Ashley Targonski:

I think what's great about what you're talking about is it's a perspective that not a lot of our other speakers have because they have been in the industry for a while. So, hearing from someone who is newer in the industry, you've gone through all of this, I think it's going to be so interesting to hear you talk about that. And I think that's one of the main reasons we're doing this conference is to have real talks about the industry and really dive into these topics that you wouldn't normally hear.

Amanda Godreau:

I really struggled with figuring out what to talk about because, ideally a presentation, a 40, 50-minute presentation about my work would be amazing. But if I have faith in myself that I'm going to have a very long and probably great career, there's going to be so many more opportunities for me to do that. I think right now, we have a gigantic young workforce that really needs their voice to be heard. Even though this is just my perspective and my interpretation, hopefully, it's a great starting point to get the conversation going. That's my goal.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, I love that. Getting back into some of the work, what was it? So, you started doing graphic design when you switched to Ringling, and then a professor pulled you into animation, and pretty immediately, you headed to the 3D space?

Amanda Godreau:

No, I think we did 3D in our second year. So, the year that the world shut down in the spring, we took one introductory 3D class that was mandatory. I didn't even know 3D existed. I just fell into the course, and I was like, "Oh, this is so amazing."

Apart from coding, I was really invested in photography. When I started using 3D and Cinema- 4D, it felt natural. I could understand light, and the physics of it because I'd had to think about strobes, posing, etc. It felt a lot more familiar to me than traditional After Effects animation. I've always considered myself a designer, and I felt like there were infinitely more possibilities for me to design in a 3D space than a two-dimensional one without having also to animate. Animating is cool, it's just not my first love.

Meryn Hayes:

I love that. And I mean, it definitely seems like a natural progression of where your interests and your skills lie. And so, heading into a 3D direction, how have you been able to find clients as you started freelancing?

Amanda Godreau:

I’ve been really fortunate to have had an amazing and generous network that got me up an running while I was in school. It was a very, I think, organic thing. Post grad I’ve enjoyed collaborating with the small businesses that I've been working with independently and that’s been a different experience. It’s a very meticulous, and consistent effort. I have this gigantic spreadsheet, and I did so much outreach trying not to sound like a spam email, essentially me being like, "Hey, work with me. I won't charge you or I'll charge you pennies." And they're like, "This isn't real."

I think I get a lot of young people who are still in college or while I was in college and they're like, "Would you recommend me going freelance?" And I would always say, "Absolutely not unless you have a big network of friends and colleagues” it’s a risky career move that requires you to be savvy not just creatively but financially.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, absolutely. Well, that's why I got to think, again, as someone who hasn't freelanced, that just so much of it is about the connections you make. And so, going freelance right out of college to be really successful has to be a challenge. And the amount of connections that it takes and the outreach and the upkeep, I mean, those are just things that they weren't teaching when I went to college. And I just have to think a part of, as you say, as things shift with this new generation, how we teach them has to change too. It's not as it was in the olden days.

I was just telling Ashley earlier today we got a request from a client we've never worked with. It was a recommendation from some Mographers that I talked to literally three years ago. I haven't spoken with them since or really kept up a lot and they just must have mentioned our name to this client and here we are. And so, it just goes to show that those connections and that, they really matter and making a good impression and just reminding yourself that stuff might not immediately turn into a project or a relationship, but three years down the line it might, you never know.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, that's literally what I try to remind people. And I also try to remind people that I had a very non-traditional experience. I didn't just go to art school, I went to NYU for coding, before NYU I had a little bit of a stint in a university in Puerto Rico which got interrupted by the gigantic hurricane that we got hit with. That’s what brought me to the US in the first place. Before then, I was always really interested in spreadsheets and finances and business. I assisted wedding photographers for five years from middle school to high school. So, I was really used to working with people who owned their own businesses, doing a lot of the upkeep, the follow-up. I almost feel like the creative side has been the easiest in my freelance journey.

There's so many things that are just soft skills that go hand in hand with freelancing. I almost feel like I fell into it.

Meryn Hayes:

Well, it sounds like, again, you worked really hard, but a lot of the disparate skills all connected to make this a really useful tool for you as you started. I mean, that's something that Ashley and I, producing is just a whole set of soft skills and something that if you go out freelancing without having been in-house or at an agency, you're essentially your own producer as well. And there's a reason why we exist. It's a whole job outside of the creative and not being exposed to what that entails I think sometimes causes people to start freelancing and then they think they're a failure of not being successful when they just haven't set themselves up to be successful because they didn't know it existed. You know? Don't know what you don't know.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, exactly. Producing is a whole other thing. I actually considered doing a production internship after graduating because I'm so interested in it. But again, I feel like that's just where my interest lies. Production to me is as interesting as creating and I don't think that's a very popular opinion. I might be wrong.

Meryn Hayes:

We love hearing it, we love to hear that.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah! Many of my good friends are producers. I strongly believe that the success of a creative project is dependent on the work that goes before you even start thinking about what it looks like. And I think that's pretty cool of you guys.

Ashley Targonski:

Looking at your growth path, I thought it was really interesting that you had a talk with Maxon in 2021 when you were still in school. You've also won their Rookie Award. So, I wanted to see how that journey and experience because you were so new at the Cinema 4D program, but then you're talking about it just seeing it a year later, which is amazing.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, I feel like all my experiences have been so surreal. When Maxon reached out asking me to present at their 3D Show I was like, "Are you aware that I've been using this program for under a year?" At that point.

I think I've had to constantly reinforce that I’m deserving of the opportunities that come my way. Imposter syndrome is so real. Sarah Beth did an amazing talk at the Bash last time. I think perspective is the most important thing we can have. I think my art is awesome and while I might not be the most technically experienced person in the room, I have such a passion for design, I feel like I'm very methodical in the ways that I do and that has inherent value…

It really resonated with me when you mentioned about how you appreciated the topic of which I'm speaking on about at Dash this year because it's something that compared to the rest of the lineup of the speaker, is very unique to my experience. I feel like that's how I've approached my career in general because although this is a very young industry and figuring out how people are even going to retire in this industry is a big question mark, looking at what I can give, being like, "Okay, I'm this person in this room, what can I do to not just be of use for myself, but to others?"

Ashley Targonski:

I really love that. And just I think you understand that while you're still in college and it's something that you're living by even today as you continue to grow as an artist, that's really cool because in college I was like, "I don't know what I'm doing." I'm just going with the flow.

Amanda Godreau:

No one knows. Yeah, I think it's so powerful and it's if you don't learn how to do that, especially as women, especially as a Black woman, it's so easy to undervalue yourself. "Oh, I'm not the smartest. Oh, I don't have the most years of experience. Oh, I've never done this before." I think shaping your perspective is vital to existing in this industry as someone who's not typically what you think of when you think of a CG designer.

Meryn Hayes:

That is so important. I mean, I think nobody knows what they're doing and when you figure that out, it helps a whole hell of a lot. I think as women we've spent way too much time doubting ourselves and trying to find space where normally you would be in that place of self-doubt.

Think about all the other things, all of the other time we would have, if we weren't doubting ourselves for every second of every day or every move, or how do we sound in X email? I mean, I have had to do a whole heck of a lot of unlearning to ignore those instincts. When you get in moments of self-doubt like that, where do you go? What's your headspace? How do you combat that?

Amanda Godreau:

I think I just remind myself that my career isn't that important. And I know that sounds counterproductive, but coming from a different culture where work isn't seen as the number one thing you strive for has been a huge factor. I've only lived stateside for four and a half years, and I think people forget that because they don't hear an accent.

In devaluing the amount of importance that I place on my career previously, I’ve been able to shift my headspace to, "I'm going to show up because I want to, not because I have to." At least for me, that’s flipped my mindset into being able to set better boundaries with myself and others work-wise and personally. I also have put a lot of importance into making friends with people who have nothing to do with the creative world. I have friends who are engineers and city planners, etc. Being around people who can separate my creative value from my personal value, especially this year has made the biggest difference.

It’s made me realize the importance of separating your own self-worth to what other people creatively think about you or as a professional. That's been really important.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, that's a good point. It's like we're so ingrained in our little bubble that it's a good reminder that a whole world, a whole lot of worlds exist outside of the Mograph community. And again, going back to how the world inspires art, talking with people outside of the community and talking with people in different disciplines, all of that is stuff that can give you an idea or inspire you in ways you weren't expecting. And also, it's just nice to meet people who are not the same as you.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, it's so much easier. Like, can we talk about how successful everyone in this industry is? No matter what they do. I remember last year being a senior or graduating and being like, "Oh my God, I'm so behind." I used to be so hard on myself.

It's not until I started hanging out with other people in their early twenties in other career paths, that I got a really healthy dose of, "You need to get some perspective." Because it can be really deceptive to be surrounded by, studio owners, successful freelancers, art directors, and NFT artists who all are financially doing so well.

It’s easy to forget what you do have, and what you should be grateful for. It's been so helpful for me to just sit down and be like, "You're losing perspective. You have ownership of your own time. You set your own salary. You get to pick and choose and say yes and no to work opportunities. And that's not something that most people ever get to do, period."

Meryn Hayes:

Well, I hope everyone comes to the Bash for many reasons, but I hope that that is one thing that people can take away from the Bash. I mean, back in 2021, I just feel like the honesty and the stories we got from our speakers last time were in comparison to all conferences or design festivals. It wasn't just get up there and talk about your work for 45 minutes and, "Oh, I worked with Nike and Google, and look how successful I am." But it's, "Here's why this was a challenge. Here's where I thought my career was over and then I started something new." Or fuck hustle, what TJ said, so having those honest conversations because everything's bright and shiny and if we all look successful, that's great.

But then for students who are just starting, or people just entering the industry, not even just students. You automatically feel like a failure if you're not an award-winning studio owner or you sold an NFT for a bajillion dollars. And so, that imposter syndrome is easy to walk into because you just walk into the industry doubting yourself.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, it's so bad. And like Ashley mentioned I was doing the Maxon 3D show. I won the Rookie Award. I graduated I got to have my work in Beeple’s studio opening in North Carolina. I remember that last experience so well because I felt like I couldn't look at my own work on a screen.

I felt like a complete imposter. I was like, "This isn't real.” "I don't want to look at my work." And I had to seriously sit myself down that night and be like, "What's going on? Am I the only one that feels this way? Why do I feel this way?" It’s so easy to think people don’t feel that way about their own work when you’re just experiencing them through social media. I’ve had students come up to me and say "I don't feel great, and I have to feel great to be able to do what you do." And I'm like, "The secret is I'm still learning how to feel great about it." I'm still learning how to accept it, how to not minimize my hard work, how to not just say, "It fell into my lap, or it was just luck."

And acknowledge that there were so many hours put in, so much burnout that happened. Giving yourself credit for the things you’ve accomplished is definitely something that’s been a learned skill. Despite how I might feel sometimes, I can often acknowledge that you can hold two truths at the same time.

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, I mean, even in this conversation, you said that everything fell into your lap, but you worked really hard and then the right opportunity came along. Those two things, those truths can be true.

Amanda Godreau:

Exactly. I have to catch myself all the time.

Ashley Targonski:

I think that's something I've had to also deal with a lot is imposter syndrome. And I was managing teams and I was still like, "Why are they asking me to do stuff? Because I don't know what I'm doing." And I obviously did. But I think a large thing that you're saying that I really think is great is you are meeting all these people, you're creating opportunities for yourself to have more opportunities in the future. So, just taking every chance you have to be able to have another opportunity later. I think that's so important for when you're young, but then also as you continue to grow throughout your career.

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, I mean, it reminds me of why I do what I do. Yesterday I had this amazing call with the founder of a brand. She founded a brand for this luxury fragrance spray. They've won all these awards. The founder is also Black and she's manufacturing this in the Bronx which is amazing. When I saw her brand I immediately messaged her, and I was like, "Oh my God, I love your perfume. Can I please work with you? You don't have to pay me. Can I just please help support this vision?" And I got a call with her yesterday, and she's said, "You don't know how hard I've looked for a creative that understands my perspective." "I looked everywhere. I couldn't find anyone." "How do you find other people creatives like you?"

And I remember telling her, "I don't know. I don't really know anyone like me."

That's a conversation I've had so many times. I think even last year, Meryn, when I was on Sarah Beth's Motion Coven podcast, I mentioned the number of times I get on a call where I'm the only woman there, and it’s assumed I'm the producer instead of a 3D designer."

I always ask people, "Hey, does anyone ever know another Black female 3D artist?” Looking at how big our industry is, I can't find someone who looks like me in the same feild. I don’t think that's something that everyone who does have that privilege is entirely conscious of.

Motion Design feels like a family to so many folks in it, or at least that’s a sentiment I’ve heard enough to remember. But it has to feel like that for more than a homogenous group. There was a very visible push for DEI initiatives around 2020 and George Floyd’s murder but efforts have become less and less public as time has passed.

Meryn Hayes:

Well, A, I'll see those people out personally. I think it's also how we move forward holistically for a sustained period of time. Like you said that there was this big push after George Floyd's murder. Everyone posted on social media and talked about bringing in more diverse groups and finding freelancers in communities that weren't of their own. But that push has to continue and be sustained across the entire industry. It's hard to push a rock up a hill if you're just by yourself, right? It has to be the community. And so, obviously, that's something that we've talked a lot about internally.

And I was, back in March, in CoMotion, we had a diversity and equity panel. We were talking and someone in the audience asked how we felt about the industry moving ahead, looking ahead. And I think the thing that boggles my mind is looking at the crowd at CoMotion, looking at Ringling, the minority of people in that group was white men by far. There were more women in the audience at CoMotion, and most of them were not white. And so, I have hopes looking ahead that the opportunities that people are given now, finding communities, like the animation industry can happen at earlier ages, right? In college. But the barriers of cost and equipment and finding places like SCAD or Ringling, I mean, that's a huge investment that communities don't have the opportunity to find.

Amanda Godreau:

I also think that looking at colleges specifically, art colleges, student bodies aren't the best way to project what the industry is going to look like. I think that while it's great to have hope in what student bodies look like, that's not going to change until the people doing the hiring have more knowledge, and perspective to be able to acknowledge what our biases are.

You have to acknowledge it in order to move past it. It might not seem like an issue to most people, because in theory your race, gender, or identity has nothing to do with the technical aspects and ability of doing a job. However, it leaves a gigantic void for mentorship. I want to be an art director, ideally a creative director, at some point in my career but I can't point to what that looks like for a Black woman. I can't ask anyone for advice and be like, "As a Black woman, how did you navigate x, y z to become a creative director?" There's no one that I know of for me to ask. And I've asked. I've asked every single time I'm on a call with a studio, when they ask, "Do you have any questions?" My question is, "Do you know any Black women AD’s, CDs?" I'm actively asking.

Even if I am here moving through my career, the road to success for these career paths is inherently absent.

Meryn Hayes:

Insane.

Ashley Targonski:

This ties into something we talked to Macaela from Newfangled about, but they have created a DIB section of their company. And when they work on projects, they find people in those communities who actually work on those projects and understand. They do the research; they talk to them about their experiences. And I think that's so integral to... That's what everyone should be doing. We should really be understanding, we shouldn't have this person on this project that doesn't know anything about what we're doing. Let's talk to the communities. Yeah.

Amanda Godreau:

I also think that leads to a really good opportunity to talk about possible jobs in this industry that don't exist in this industry. Because listen, I can say all day that my information is in my bio, on my website. But the truth is, producers are often also super overworked. You can't expect them to be reading the bio of every single artist that they're reaching out to. It's impossible.

I feel like that's a huge opportunity in motion design that could lead to even more jobs and a more diverse workforce. Producers do so much, they keep track of so many things.

Meryn Hayes:

I was also just re-reading Bien’s blog post for their Q&A, and they were talking about Double the Line efforts. Do you know about that program?

Amanda Godreau:

I don't!

Meryn Hayes:

It comes from the Association of Independent Producers (AICP, essentially for every job they have, they create a second line item in the budget for whatever it is, cel animation or illustration, to bring on an underrepresented minority group. So, a Black cel artist to pair with a senior cel artist so that they get opportunities to work on a project or on a client work that otherwise they wouldn't get. And then they have that as an opportunity to show on their portfolio, like, "Hey, I did this."

And so, bringing people into positions that they previously wouldn't have an opportunity because they don't have the connections yet. We talked about how important those connections are early on in finding jobs or careers.

Amanda Godreau:

That's amazing. I think that's an amazing thing for a studio to be doing. Going back to the conversation about SCAD and Ringling, I think that also has to be part of the conversation is that while it might be really convenient for studios to hire out of Ringling and SCAD because it's the standard, and you do come out industry ready. I think there are a lot of colleges and programs that are also overlooked that might have equally as amazing talent.

Last year I went to speak to the students at CUNY in Brooklyn. To my surprise when I arrived, I realized that not only was the professor Black, but so was the entire student body. Not only that but mostly black women. This was a Cinema 4D class.

I think that's the only time in my career where I've been in a room full of people who looked like me. I felt really conflicted when I left because they were there, talented, and learning with such amazing questions, and I couldn’t give them advice that was relevant to their experience. I had a huge leg up with going to a private art institution.

I carry some privileges. I feel very conflicted when I’m used as an example for someone who is a minority who’s moving through our industry. I often feel like the worst example. I went to a very expensive art school. I so happened to have my own business in high school that paid for a huge chunk of my college education. I come from a family of academics and had little to no barrier for entry when applying for college." While my experience has value, merit and includes a lot of hard work. No one should be used as a rule for "If they did it, why can’t you?"

Meryn Hayes:

Yeah, yeah. I think that's a good reminder. Just like you said that again, it's setting people up for failure, right? When you don't see all of those privileges that you know you've had and that I know I've had, and other people have had. You don't see that. And when you compare yourself to someone else, "Amanda did it, why aren't you doing it?"

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah.

Meryn Hayes:

Thank you. We're just so glad to have you come in and really can't thank you enough for participating, being willing, and we're looking forward to your talk!

Amanda Godreau:

I'm so excited. This is my favorite conference.

Ashley Targonski:

Can we quote you on that?

Amanda Godreau:

Yeah, totally.

Meryn Hayes:

It's going to be the Bash, the homepage. It's going to be a huge quote. Amanda says...”MY FAVORITE CONFERENCE”

Meryn Hayes:

Cool. Good chatting, Amanda. We'll see you soon!

Meet the speakers: Wes Louis

An interview with Wes Louis: a director, designer, and animator at The Line known for his unique design sensibility and his dramatic action-led animation sequences.

Q&A hosted by Mack Garrison.

Read time: 15min

Mack Garrison:

Wesley, I'm really pumped for this conversation because, well, one, if you don't know this already, you guys do phenomenal work. I mean, the cel work you guys produce, just really top tier, top quality.

Wes Louis:

Thank you, man, I appreciate that.

Mack Garrison:

I was talking to Dotti over at Golden Wolf, because she was at the Bash last time. She spoke on behalf of Golden Wolf there. She was talking about how highly she thinks of you guys and that for a long time you kept winning and losing to each other on pitches. It was just always you guys going back and forth.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, that is exactly right. They would do something and then we would do something, and they would do something but it feels kind of healthy. It's strange to say, because you think to yourself, "Well, I mean they are a rival company," but actually we have quite a good relationship with them. Anytime they have their summer parties or other events, they invite us over. We have a good laugh and a few drinks, so it's a healthy competitive space.

Mack Garrison:

I remember getting out of school and being so green in this space, not knowing anything, but how many people were willing to help me. Even growing from junior up to senior as an animator, and then again, starting the studio, and how people were just willing to share advice. I've never met a space that feels as communal as the motion design space really is.

Wes Louis:

I just think it’s what makes the space a better place to work in. No one's holding their cards too close to their chest. It's weird, because intuitively you’d think keeping what's unique about you secret would be the way to go but, the opposite has benefits. One of our other directors, Sam, always talks to guys from Animade or Moth Collective about all sorts. We all go to the same festivals, hang out and talk. "Well how did you do that or show the best way to do this?" it's a weird but nice little community we have

Mack Garrison:

It feels different, because I feel like it's not like that in the rest of the creative space. Even agencies, I know agencies are kind of cutthroat with each other, but studios, for whatever reason, it's not. I think it's because, as a studio owner, I feel like people start studios because they really love a singular craft.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, exactly, you're coming from the same place. And I think with us specifically, because all the directors of the company, we're all animators or compositors, we all come from creative backgrounds. I think we just have more of an understanding of people that work with us as well. So we understand burnout, we understand what it feels like not to want to work on something that maybe you're not feeling inspired by.

Mack Garrison:

So I run Dash with a business partner. We were both animators back in the day. We animated for basically a decade before trying our hand at running a shop and I think there's a difference. When leadership knows how to animate, you don't put your team in bad situations. Even just understanding what's reasonable, what's not, what's a hard request, what's not, and to be able to talk through that. I think you get into trouble when it gets too much on the business-oriented side of things.

Wes Louis:

Definitely. We worked on a Gorillaz music video with Jamie Hewlett. The turnaround for that, I think it was something ridiculous, six or eight weeks, and we did it because, I mean, it's the Gorillaz….

Mack Garrison:

This is the Humility piece, right?

Wes Louis:

Yeah.

Mack Garrison:

That you did that in 6 weeks. That's ridiculous.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, it was crazy. It was like a six-week turnaround to get everything done. Max and Tim were directing it. Tim's a massive Jamie Hewlett fan, so that's like a dream come true project just landing on his plate. We took the job, but I think everybody, including the directors, worked so hard on it. They were working late, working until 10 o'clock at night and all that kinds. We really understood what our staff was going through and I think they appreciated that we acknowledged that we were pushing them to the limit, but then we also said, "We're never doing that again," because you're breaking the people that are working for you. So while The project gave the studio a lot of street cred, it also made us really examine our working practices because the people who work for us are important. I mean animation is hard enough as it is without you having to come home after hours every night and you're not spending time with your friends and family. So you want to try and find a balance. I mean, sometimes it happens where a crunch happens and you have to stay a bit later, but I think nine times out of 10 it's definitely more of an exception than a rule. Whereas I know some companies are like, "No, you've got to work on the weekend and you've got to work on this, you've got to work that." We try not to do that.

Mack Garrison:

A hundred percent. We feel the same way. And I think part of it was also that self-reflection after the pandemic where priorities just totally switched for people. It's like, "Look, this is just a job." We like it, I love animation, but there's stuff outside of it. We all have stuff outside of it, right?

Mack Garrison:

I want to get back into some of the stuff you guys are doing at Line, because like I said, it's phenomenal. But maybe take me back to the beginning.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, so my family's Caribbean, St. Lucian. My parents were born over there. But I was born and raised here in London. As a child I was always into animation, just generally, Saturday morning cartoons, anime shows. I'd always been drawn well. I've been drawing since I was five-years-old... and never really put it down. So it was something that I think people thought it would just be a hobby that went away, and it never did. I was doing anything that could probably lead me into comics or animation, any excuse to draw. Graphic design was the closest thing I could find to do that. And even on graphic design projects, I was always trying to do some sort of character design or animation orientated thing. But yeah, I studied multimedia for a bit and I dropped out of that because I just wasn't happy doing the course, so I spent a few years working in retail and doing office work and all this stuff. And I think it was like 27, that I just asked myself the question, "If money and logistics weren't a factor, what would I be doing?" And animation just kept coming back, so I kind of worked my way backwards and just started saving for it and doing odd jobs so I can save money, so I could take a year or two off just so I can do a course in animation.

Mack Garrison:

So you did graphic design, you kind of dropped out of the multimedia side because you weren't vibing with it as much. You wanted to get more into the traditional, kind of cel animation. Is that what was drawing your interest mainly?

Wes Louis:

Yeah that's what it is. Even when I was doing retail, I remember I was working in a store called Hamleys, it's like a toy store, a big toy store in London on Regent Street. And I remember they would ask me to do graphic design things every now and then, but I was working behind the tills. And I remember applying for a job in the display department, where they would decorate displays and all that kind of stuff. And I thought, "Yeah, this would be perfect." And it's funny, the head of display, showed him my CV, showed my work. He is like, "Yeah, you're amazing," all this kind stuff. He's like, "But I'm not going to give you a job." I was like, "Why?" "Because you're too good for here." I was like, "Why?. He is like, "If you want to go and work in this, then get off your ass and go and find somewhere to work, but I'm not giving you a job here." And he refused to give me a job.

Mack Garrison:

Wow.

Wes Louis:

Yeah. There was also a point where I tried to go full-time in Hamleys, because I was working three or four days a week, and my manager at the time refused to give me a job. She refused to let me work full-time. I was like, "What's going on?" She goes, "Oh, I see you..." Because I would do a lot of doodles on till receipt paper while I'm waiting for customers. I've still got loads of them at home. She was like, "I always see you drawing on these receipts and you're just sitting here." And she goes, "Why aren't you going out and looking for real work in what you love?" I didn't really have a proper answer for her, because I was quite young at the time. But she's like, "Look, I'm not giving you a job here." She goes, "If you want to work a few days a week, that's fine, I can't stop you but don't try and apply for any other department, because if you try and apply, I'm going to tell them not to hire you."

Mack Garrison:

No way.

Wes Louis:

They just literally would not let me work full time there.

Mack Garrison:

That's so crazy. It's that early confidence push and kind of validation that what you're doing, what you're creating means something.

Wes Louis:

I think that's what it was. I actually did reach out to her (Her name is Julia) just to tell her thank you for doing that, pushing me. So I think from then I just went into work with more of a focus. I made a decision to become an animator and spent time working and saving up for a Postgraduate animation course at Central Saint Martins in London. It's funny, because when I went to visit the college they'd had the end of year show, and for some reason, that year it was incredible. So I worked so hard to get on that course, man, believing I wasn't good enough to get on the course. I was doing life drawing classes every weekend. I think I was doing it twice a week. And I went on to an art exchange program in Prague with conceptart.org, hosted by a company called Massive Black.

Mack Garrison:

Well it had to be good validation for you on this career path too, because I know when you find something you're really into, you get into this flow state where it's not work anymore. It's all this stuff that you're trying to get better at and it's hard, but it's fun. You're excited, you want to jump in and just learn as much as you can. It's a totally different vibe versus if you're in something you're not digging.

Wes Louis:

Oh, I think that's 100% true. And I could even point to projects I've done where I know the flow state versus not being in a flow state, for sure.

I did a lot of work to get on the course. I even visited the university a couple of times to speak to the head lecturer just to talk. "Ah," he goes, "you again." So I would go up there, spend about 20 minutes with him, keep in mind I lived an hour away from the university at the time. I'm showing him my sketchbook just asking questions “is this good? Do I need to draw more of this?” It really was an excuse to be in that environment with lightboxes and students flippings animation paper. It was the closest thing to an animation studio I'd ever been in and I loved it. By the time I had my interview he was just like, "All right, well let's see how we can get rid of you then." But he was joking, very British humor. He said, "Your portfolio is incredible. What took you so long," sort of thing. So he was like, "Of course we want you on the course.

Mack Garrison:

Right.

Wes Louis:

I had worked so hard to get on the course, because I just thought I wasn't good enough so I didn't take it for granted. I studied for a year. That's where I met Tim McCourt, who was on the same course as me. After the course finished, I spent about six months trying to finish my thesis film, which I didn't.

Mack Garrison:

That's great.

Wes Louis:

I really tried to finish. I thought there was something wrong with me because it was like, "Why can't I finish this?" And I was trying to get a certain amount of quality in a certain amount of time, but I just couldn't do it. Just not realizing that, actually animation takes time and it takes a team. And I'm trying to do this, Disney level stuff by myself.

Mack Garrison:

That's a lot. That's a lot to put on your plate. So you never finished the thesis?

Wes Louis:

No, I didn't finish but I really tried. I worked on it for a few months after the course but it was so much harder trying to do it from home. About 6 months after uni,I moved to Scotland. I was working at a company called Ink Digital on this film called Illusionist, as an inbetweener cleanup artist. I even tried to finish my thesis film there, redesigned the characters and everything. Even at that point, I wasn't very confident in animation. I just couldn't understand how to do it. I remember meeting with an animator at Django Films (that was the main studio for the Illusionist where all the animation took place) She gracefully took time out to show me around and show me her work and process. Within half an hour she said and My understanding of animation completely changed. If you asked me to do my thesis film today, be it two months or three months I’d finish it. I’d know what to animate, what to cheat etc.

Mack Garrison:

What did she say to you?

Wes Louis:

I said, "So what's your breakdown?" She goes, "I don't really think about it that way, I just do the motion. And then I find a breakdown afterwards." She showed me her sketches and demonstrated her method. It just made sense. It was Aya Suzuki, actually. She's gone on to work with directors like Hayo Myazakiand she's an incredible animator. It was just a half an hour chat and it was like things clicked all of a sudden where the things that I was struggling to do weren't hard anymore, because now I understood what it was. And it was just basically her process of how she put an idea down and got the movement down. I think my problem was getting too in the weeds of it, I was trying to understand what's a breakdown, what's a key. I think those things matter when you're passing off the animation to somebody else, but when you're doing it yourself, it doesn't matter that much, you know? There might be some people that disagree with me, but that was just for me, it just made sense the way she went about it.

Mack Garrison:

Tell me about some of the projects that came after that?

Wes Louis:

So when I got back from Scotland, I met up with Tim again and we worked on our first short film together. We spent about a year doing that at a Partizan. We were very fortunate to have a space to work for free as Tim had a good relationship with one of the producers at the time. We thought it would take us three months, it took us about a year. And we got an award from the Westminster Arts Council. So they were giving out money for people to make films and stuff... so I think they gave us 4,000 pounds, which seemed like a lot at the time.

Mack Garrison:

Yeah, of course.

Wes Louis:

I mean, me and Tim weren't getting paid for it, we were doing freelance work for Partizan so we could keep on going. We learnt a lot doing that. After that I guess the project that made me more well known was Super Turbo Atomic Ninja Rabbit, I just went full steam ahead. It was a style of animation I'd never approached before. I've never done anything like it which is ironic because my love of animation really is rooted in action and anime. There was no reason for me to think I could do it except that I just wanted to so I just went ahead and tried. Also got a friend Rina May to do the music and BXFTYS on sound fx. Actually let me backup, I'm jumping around a bit. After me and Tim made our film, we went around looking for work as directors. Turns out it doesn't really work in that way. You don't just go and apply to be a director.

Mack Garrison:

Yeah, right. Like, "I'd like to work here please." And it's like, "No, thank you."

Wes Louis:

Yeah, yeah. "I'd like to work as a director." It's like, "Not really, no."

Mack Garrison:

That's great.

Wes Louis:

I did show my portfolio though and a few weeks later it was like, "Oh, yeah, we like your work we have some jobs on if you're interested. That was at Nexus in London." And I was working there freelance for about a year and Tim was doing freelance at Partizan and some other places. While Tim was on the job, he met with Sam Taylor, James Duveen and Bjorn Erik Aschim, the other partners at The Line. Sam was looking for a studio space at the time and was asking if we were interested in sharing a space, and not even as a company but just people who animate together and have a shared space while working different freelance jobs. I couldn’t really afford it at the time but we had a friend Fritzi who had a desk and she was letting me use it at the time and eventually I took over from her. While at the studio Tim got approached by some of the runners who were at Partizan who now have their own company, Bullion Productions. They got a job from the Ministry of Sound to do a music video for Mat Zo and Porter Robinson and asked if Tim and I were up for directing because they knew we made our short film at Partizan. So it was like, "Yeah, sure." And then the other guys we were sharing a space with, they were just finishing up their film Everything I can See From Here, so we were like, "Oh, if you guys aren't doing anything, we'd like to hire you to work on our project." So the six of us worked on this project together and it went so well. It was an incredible experience. We just said, "Oh, how about we start a collective, we can just consolidate our work and take it further?" That's basically when we formed The Line.

Mack Garrison:

It's perfect.

Wes Louis:

Soon after Bjorn got contacted by Electric Theatre Collective (ETC) to do some concept art and they were asking, "Do you know any animators or character designers?" He's like, "Oh, I actually know five guys."

So we went over there and we were working together for a while. They gave us some funding to make our first official The Line original projects. Amaro and Walden's Joyride and Super Turbo Atomic Ninja Rabbit. Ideas we had for a couple years. We were working on those productions simultaneously and released them a month apart, maybe two. I think that these projects gave us our notoriety. From then we just started getting commercial projects. We were at ETC for about 3 years I think but eventually ended up leaving to actually start our own studio. No hard feelings or anything, it just became harder to function the way we wanted to as directors. We thought, "Let's see if we can start our own company." I mean the options then were, to either leave and try and make some more money to build ourselves back up, and then hopefully regroup again, which probably wouldn't have happened. Or let's just go for it and start a company. So we pooled some money together, got a studio space and our first job came within 2 months and….

Mack Garrison:

The rest is history.

Wes Louis:

... five years later we've got, I think about we have roughly 40 people with us including the 6 founders.

Mack Garrison:

Man, that's crazy.

Wes Louis:

James counted about, over three or four projects, we had about 110 people working with us at one time.

Mack Garrison:

Wow. That's crazy.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, it is a bit surreal, because you're looking around and you're like- "I don't exactly know how this works but it is working, and it's great."

Mack Garrison:

Oh, no, it's really cool. So a couple of things I picked up on there, Wesley that I think is really interesting and I want to poke at a bit is, so you get out of school, you end up on this Illusionist project, you're kind of navigating the process a bit, but then it kind of starts to click. You and Tim, then after the Illusionist, work on your personal project, right. What film was that that you guys were doing?

Wes Louis:

Drawing Inspiration.

Mack Garrison:

Drawing Inspiration, that's right. So you're doing these films or this entertainment side of things and then you end up from that side into kind of the commercial space a bit from there. But I like how when you even refer to the projects you're working on, you're referring to them as films. Everything you do has this artistic lens. And I do think there's this balance in animation with art versus design, right?

Wes Louis:

Yeah.

Mack Garrison:

How did you navigate that as you got into that world and all of a sudden these projects, which I'm sure you had thoughts on, on how you want it to be, is now getting pushback from clients who are paying you for it and they want it done a certain way and you're like, "That's killing the artistic style of it." How does the artist versus designer kind of come into play for you these days?

Wes Louis:

That's a really interesting question. I mean even the short films that we made, people ask, "How do you make the time to make those films and do what you want? It's insane." And the answer is, it is insane. It sounds very cliche, but we were too stupid to know that you're not supposed to do these kinds of things. We made two short films in a year simultaneously, while trying to do freelance projects. And that's crazy, because I was working, I mean we were working weekends, evenings and stuff, and it's not an easy thing to do. But like you said, if you love what you're doing, you don't really perceive it as work, you just perceive it as this thing that you need to get done.

In terms of the commercial side, I think earlier on I would say we did get projects that you'd get weird client pushback. I remember doing a project and I literally had the clients standing behind me while I was doing a drawing.

Mack Garrison:

No! I would've quit. I would've been out.

Wes Louis:

Oh god, it was like the Apprentice. There were about three or four of them and I was drawing a face. "Oh, do this in the lips. Move it, move it. No, push it up, push it down. Make her eyes bigger. Make it smaller." And the drawing, at the end of it, I just remember sitting there thinking, "This is not going in my portfolio, this is the worst piece of work I've ever done.”

And luckily, I mean they kind of doubled back and they were like, "Oh, actually, this is not working." And then I had to redesign it from scratch and they just kind of left us to it. But actually, generally speaking, I feel like our clients have been really good. And I think that's because of the short films that we've made. And I think the thing that we realize is, if we make the things that we want to make and make it high quality, people hopefully will come to us for what we do rather than what someone else does. And I think that brings about a certain amount of trust from our client as well. So if we show them something that we've done that they're interested in. So anytime we get a pitch in, well a lot of the times they will point to other people's work, but it will always have our work in there. "Oh, when you did this on this project, this was great. We'd love more of this and stuff."

Mack Garrison:

It's almost like, concept-wise with references to other things, but stylistically it always comes back to you all. So you know you're in the right lane.

Wes Louis:

Yeah. So actually when we are doing stuff, nine times out of ten, I would say you do get satisfaction from the client work. Obviously it's not going to be 100% your way and I think there's an expectation of that. Look, someone's paying you to do this and you put your best foot forward and say, "Look, I really don't think this is a good idea because," and they do listen and then sometimes it's someone higher than the person you're talking to is like, "No, we definitely want this." "Oh, okay, that's fine." I always take our client projects as a space to learn as well.

Mack Garrison:

Sure, sure.

Wes Louis:

I'm getting paid to learn how to do something a little bit differently and apply it to my own work and to the studio as well. I mean the whole reason we started it is so that we can make our own stuff. We actually put some of our profits back into personal and development projects. We’ve actually got a few in development at the moment and one hopefully dropping late-summer.

Mack Garrison:

Perfect. That will be a perfect time to roll it in for the summer and share it on the big screen here in Raleigh.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, exactly. It's a short. Our films are quite short so typically they’re made in the style of a trailer or a music video, because to try and do anything longer can be quite difficult if you want something really long form. Doing shorts like this gives us a chance to kind of put stuff out there, our own identity and have people in the studio play around on things that they probably wouldn't normally get to do at other studios. We've actually got another director, who is the first director doing a personal project outside of the six of us.

Mack Garrison:

How does that feel? Because I do think there's something about as you progress as a studio or owner, you can't have your hand in everything. You can't always see stuff. Does it feel weird to get to this space where there's a director kind of rolling with something and you're not really sure what's going on?

Wes Louis:

It's weird. I think even just not being hands-on is a little bit frustrating for me. I got into it so I can draw and animate and I'm not drawing and animating anymore. And even people have said to me, "Oh, I don't really see your work anymore." It really is rewarding though, to see an animator go from a junior assist role to directing a project on her own project; leading a team of people, having her own voice and having the respect of all her peers supporting her, I think is amazing. I think none of us are under the illusion that we're always going to be relevant and it's nice to be able to build a space with the resources we have that can trickle down to the next generation. And they create stuff, and they do better than we ever could.

Mack Garrison:

I think, well because you look back and you look at the stuff that you've gone through and you learn about things that you really liked and the people that pushed you. Even your retail boss, don't do this, or your colleague who's like, "Think about it this way," and there's all these moments with these spaces where that's conducive. And so I think as leaders, you try to create that space at your studio. What are the things that you really wanted? What are the things that you can create an area for someone to try stuff to fail and stuff to grow and to learn? And so that's got to be a huge highlight at The Line.

Wes Louis:

Yeah, it is something that I think we speak about we're proud of. I mean, we don't always get everything right, we're still learning.

Mack Garrison:

Sure.

Wes Louis:

But I think more often than not from what people have said, unless they're lying to us, they're comfortable working or they like it, they feel supported, they feel like they've been heard and they get to put their ideas across. We've got this initiative that our development manager has put forward. So basically, we give 10 days to each person on the staff every year to just go in and play. The caveat is that it has to benefit the company in some sort of way. So it could be they go in, find a new system for production or just learn how to draw something a little bit better. Anything they want. It doesn't have to be something they present, it's just 10 days for people to go and play, because sometimes you wait for downtime to happen and sometimes there is no downtime. So it's like, all right, here's 10 days. And actually, some of the projects that we're working on now came from that. In fact, there's about three projects that have come from our exploration time where people have gone away, had 10 days to think about something that they weren't thinking about before, and then they've come back and said, "Oh, actually, I've got a great idea." It's like, "All right, let's make that, let's put some money into that so you get to have a bit of a creative outlet.

Mack Garrison:

That's cool. I love that. And I love the buy-in from folks too, because it makes people feel like they're bought into the studio. They're bringing their ideas to the table and the studio's rallying around them, which is really nice too.

Wes Louis:

I think that the thing with us is that we're like, "Oh, it would be so cool if we had this when we were coming up." We're like, "All right, well let's just do it for our staff." And it seems to be working.

Mack Garrison:

Do y'all feel good where you are now or do you want to continue to expand? Do you have any big, broader goals for the company?

Wes Louis:

It's funny you say that, because we literally are in a kind of space where we're trying to reestablish and just remember where we came from and use that to inform where we're going. So I'm from the Caribbean, as I said before, and what I've been doing is I've started this kind of program with a company in Jamaica called ListenMi, they're an animation company. And basically I just give them an hour a week or hour every two weeks of my time just sharing insight into just how animation works and helping them, in a sense, kind of level up. Because I think you've got loads of animators or aspiring animators in the Caribbean who just don't have the resources or people to teach them.

And I know I learn a lot because I've spoken to people around me and I've got access to certain things. And I guess for me personally, I would love The Line to be one of these spaces where, I don't know, it has some sort of academic program, training, and internship. And that's something that I have started trying out. I don't know where it's going to go. I feel like this is something that could take the next 10 years, it could take 20 years or something, I don't know. But I do recognize that, for instance, you've got places like Korea where the American animation was being outsourced to them and now they've just got incredible studios like Studio Mir for example. I think that's how you grow an industry. And I feel like the dream for me would be, reaching out to these places and training them up so that they can start. Eventually, we can outsource work to them and they grow and get better. And then they can start creating their own works, and then it trickles down to the schools and now you've got a thriving industry. So that's the kind of influence I would like the company to have.

Mack Garrison: